|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Wynn Jones | |||||||||||||||||||||

| gallery 4 - archive | |||||||||||||||||||||

| gallery 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 |

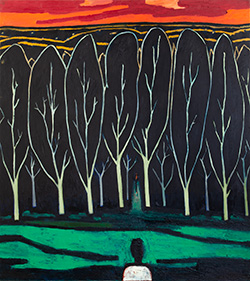

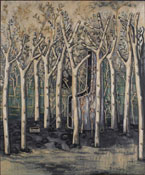

Nicholas Usherwood writes: Born and brought up in a small Welsh village Wynn Jones’ family home was directly across the road from the Methodist Chapel and some of his earliest memories are of the regular, solemn tread of the funeral processions making their way past the house on the way to the tree-lined cemetery that overlooked the village – and the singing! It was this early and constant awareness of death allied to the shape-changing legends of traditional Welsh folk-tales that ensured an encounter with mortality, ritual and myth that remains embedded in his work to this day but, at the time, the experience of this claustrophobic place and way of life was one that he looked to get away from at the earliest possible moment. That opportunity came, aged 17, in the form of art-school, first in Cardiff and then on a Mellon Foundation Scholarship to the Byam Shaw School of Art in London, but the journey back into these memories and their transformation into poetical, mythical meaning is one that has taken the next 45 years of his painting life to come to terms with. Indeed it is really only now, in the paintings of the last 10 years or so that he feels they have acquired the humanity and fullness of experience he would expect of them and, in Rilke’s resonant phrase, finally begun to turn “to blood within us, to gesture, nameless and no longer to be distinguished from ourselves”, as the outpouring of one astonishingly powerful and memorable image after another here bears eloquent testament.

Jones feels now this sense of a journey is one that has always pervaded his work in some form or other, though, as the four earlier paintings accompanying this text confirm, it is only now, in the many entrances, passages and crossings, journeys “over territories ancient and mysterious” that mark these most recent paintings so particularly, has his work perhaps truly begun to resolve itself with the kind of inevitability of form and poetic content he would wish for them. The journey has, in truth, become an entirely metaphorical one, the re-visiting of the landscape of his childhood absolutely nothing to do with any sense of nostalgic longing but rather one of imaginative transformation, the “stage” so to speak, for the troupe of riders and racers, singers, sowers and celebrants who inhabit the spaces and who owe their many and varied forms to the painter’s parallel journey through the complex and enduring nature of figurative painting. Jones has a deep sense of history and of European culture, which informs his commitment to an expressive, sometimes extreme form of figuration.

In their unlikely and somehow unexpected admixture of high theatricality and human comedy with elements of unmistakable tragedy, pathos and farce, they are not always easy images to come to terms with, hitting you initially with a force which you are unaccustomed to in so much emotionally evasive contemporary painting. But start to think in terms of Dante, Giotto, Goya, Watteau, the burlesque drawings of Domenico Tiepolo Philip Guston’s later paintings or even, within 20thC. theatre, of the “gallows humour” of Samuel Beckett’s interior world, and you begin to get closer to the sense of these extraordinary works. Jones is, rightly, reluctant to discuss the specific content and subject matter, believing the titles he has so carefully given to each have to act as clues, after which it is up to each viewer to work at what the painting can mean for him. As the painter Ken Kiff once wrote to him “Images that can have meaning for other people can only come from sources deep within oneself. If they come from these sources other people share them.” Jones talks about the intensely personal rhythms of painting as a dialogue that includes “going beyond the surface to deeper levels that draw in and pool together impressions and experiences from a sort of unforced gathering of the arbitrary and intuitive; allowing these surprising and unexpected forces into the creative act can energise and revitalise it”. What I believe is important both for him and for us in these paintings is the feeling and sensation they convey, above all the sense of inwardness, or controlled passion as he prefers to put it, in which the candles, torches or flares that form such a key element in so many paintings here both illuminate the journey being taken and evoke a powerful sense not only of the sacred but, at times also, of rather darker forces. In the process he succeeds in creating a kind of counterpoint of light and dark, of the illuminated and still hidden and shadowy, that is close to the musical in its abstract effect.

Finally, in this context, it should be made clear what an increasingly vital role colour has come to play particularly in the work of the last five years. As the paintings in the first section of the website show, even as late as 2000, Jones was using a comparatively subdued palette of earth greens, greys and black, often very thinly painted. Then, really quite suddenly, there was an explosion of uninhibited, visceral colour, often unmodulated and highly saturated – glowing reds, oranges and yellows offset by cerulean blue and emerald green and the inevitable signature black, colours that begin to play a much more central role in driving the pictures forward, symbolic in themselves of matters celebratory and sorrowful, poetic and spiritual. A word also about the importance to his working process of the smaller, mixed media works on paper (illustrated here in Gallery 3), which are, effectively, the drawing process for the larger oils. My sense of their function is that they act as a kind of seed-bed for the quite extraordinary images that find their way on to the larger canvases, powerful single images which don’t have to fight the others for the artist’s attention to come into existence. As Philip Guston once described it “The forms having known one another differently before, advance yet again, their gravity marked by their escape from inertia… a painting is finished when it feels not new but old. As if the forms have lived a long time within you…it is the looker, not the maker, who is hungry for the new.” It is just this sense of recognising within them something also deep within your own subconscious memory that finally makes these paintings so profoundly serious and significant for the present moment. Jones believes “painting is a serious, moral business that can also smile, though that smile is often rueful, sometimes melancholy, occasionally manic. Painting is never a metaphorical shrug of the shoulders.” In its attachment to the sacred and its celebration of myth his painting makes connections to our most ancient origins, restating those fundamental principles which, like Jones, I feel, have quite as much to do with the essential truthfulness of our life and understanding of the real nature of our world as any scientific discovery.

Nicholas Usherwood is features editor of Galleries magazine. His recent publications include monographs on Evelyn Williams and Norman Adams. |